After tackling transportation and education in recent sessions, King County legislators are expecting 2019 to be a big year for housing.

State Sen. Guy Palumbo (D-Maltby), who represents the fast-growing 1st Legislative District, including areas of Kirkland, Bothell and south Snohomish County, said there’s momentum on the issue in Olympia.

“The housing and homelessness crisis has really brought this issue to the fore,” Palumbo said. “Going into next year, I think there’s a wide recognition across the aisle and certainly in our caucus that we have to address this at a state level as well as the local level.”

Palumbo noted that legislators in both chambers and both parties are preparing different types of bills to address the housing shortage and affordability crisis, which has been caused by growth and exacerbated by outdated policies, he said.

“We’re at a unique point in time,” he said. “Right now, everybody’s pretty much saying the same thing: we have to build more housing… There’s an urgency to get something done among factions that don’t always get along.”

Palumbo said he anticipates movement on both the funding and policy sides. He is also sponsoring a minimum density bill and a short plat bill — policies that aim to reform the 28-year-old Growth Management Act (GMA) — and predicted that the Legislature will put a lot more money into the Housing Trust Fund this year.

Palumbo and Sen. Mark Mullet (D-Issaquah) were vocal opponents of Seattle’s proposed head tax that would have raised money for homelessness, but suggested different funding sources on the state level. Seattle area legislators are working on eviction prevention, SEPA reforms and accessory dwelling units.

State Rep. Tana Senn (D-Mercer Island) and Sen. Jamie Pedersen (D-Seattle) are sponsoring a companion bill in the House and Senate for condo liability reform.

“The Puget Sound region is experiencing a shortage of condominiums being built and sold, especially those at an affordable price point,” according to an issue brief by the Bellevue-based Master Builders Association of King and Snohomish Counties (MBAKS) from January 2018.

Senn said that “when you look at the housing crisis, one of the key components is condominiums for both the entry and the exit.”

“If you think about people getting into the housing market, they want to build equity by buying a lower price condominium so they can then sell that and move into a bigger house,” she said. “And on the other spectrum, you have people like elderly neighbors who might want to be downsizing and moving into a condominium, but there’s just nothing available. So they stay in their homes, and that blocks people from moving, and that drives up the prices.”

Palumbo was one of the speakers at the MBAKS Housing Solution Breakfast on Oct. 24, where the homebuilding organization unveiled its legislative priorities. They include condo liability reform and other “legislative solutions designed to increase housing supply and eliminate unnecessary and costly hurdles to new home construction, without compromising environmental or consumer protections.”

The Washington State Condominium Act, adopted in 1989, caused a “risky and unpredictable” condo market by placing “significant liability on builders,” according to MBAKS.

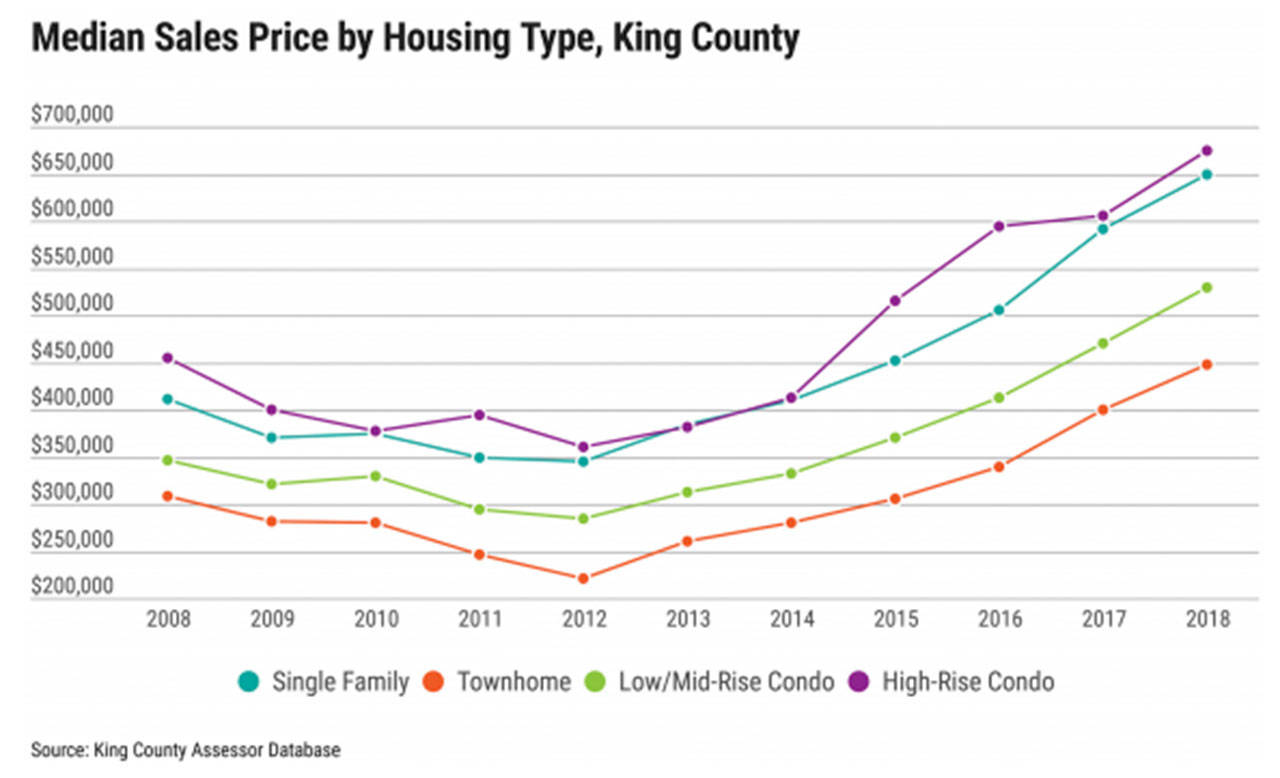

Many believe the act overprotects consumers, so the only developers willing to take the risk are those building luxury units. In 2015, the median price of a new condominium in Seattle was $683,590. Senn’s HB 2831, which died in committee last year, would have addressed some of the issues with expensive litigation.

Senn’s goal with legislation is to reduce insurance costs “and for people to look at the development of condominiums not as a likely problem,” motivating both to come back into the market.

“This is not about reducing quality or consumer protections,” she said. “This is about righting the liability equation.”

Condominiums, townhouses, duplexes, triplexes, quadplexes and backyard apartments are part of the “missing middle” in Seattle’s housing types, Palumbo said.

“Right now, we don’t really solve for all income levels,” he said. “In Seattle, you’re solved for if you have an apartment… or if you want a really expensive single-family house, and there’s nothing in the middle.”

If other types of housing aren’t encouraged in an area’s biggest city, and biggest job center, the result is suburban sprawl, he said. For Palumbo, there are two solutions: make cities give up local control to force more density, or provide infrastructure to the suburbs, especially unincorporated areas. Organizations like the Association of Washington Cities (AWC) are opposed to his bill, but he aims to work collaboratively with all constituents on the legislation, he said, and to fix what’s “broken” in the GMA.

“[The GMA] wasn’t meant to be perfect. It’s extremely complicated. It’s done a good job of concentrating growth inside UGAs (urban growth areas). However, we’re acutely feeling the effects of where certain things break,” he said.

Palumbo’s goal is to make sure his communities receive their fair share of infrastructure funding to keep up with population growth.

“This thing with Seattle not taking the density it should, because it’s all zoned single family, is causing trouble in the suburbs. It’s pushing people out because they have to drive to qualify,” he said.

The Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC), which is tasked with planning for regional growth, agrees that “middle” housing is scarce in the region.

A recent PRSC report concluded that while middle housing is more affordable than single-family, the region’s ownership housing stock is dominated by traditional detached single-family housing; it represents 81 percent of the ownership housing stock in King County, and 86 percent of the stock in Kitsap, Pierce and Snohomish counties combined.

PRSC is planning for an additional 1.8 million people and 1.2 jobs by 2050.