The Herbert H. Warrick Jr. Museum of Communications may well be the only place where you can see, all together, a replica of Alexander Graham Bell’s first telephone of 1876, teletypes used by the press, a Western Electric Panel Switch from 1923 and an iconic red British telephone booth.

The first words spoken through that first telephone were Alexander Graham Bell’s: “Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you.”

Most all equipment is fully operational and includes everything from switchboards to linemen’s tools, early telephone sets and amateur radios — even glass knobs from telephone poles.

The museum, located in Seattle, is named for a Mercer Island resident.

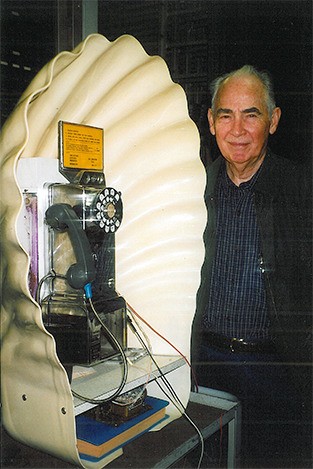

An open house was held at the museum last month in memory of Herbert Warrick, Jr., who died Oct. 2, 2012, at age 89.

Warrick, an army veteran of World War II, had a lifetime career in telecommunications and founded the museum in 1986. His initial vision was to establish three Telephone Pioneer museums in Seattle, Spokane and Portland, but only the Seattle location materialized.

Pacific Northwest Bell provided the building space in the Duwamish Central Office, and the museum became The Vintage Telephone Equipment Museum.

This year, the museum has taken on Warrick’s name.

“Though Herb was always quick to downplay his importance (he always insisted that credit be given to the hard work and dedication of museum volunteers), we could not have done it without Herb,” Don Ostrand, the museum curator, stated. “In honor of that effort and in coordination with Herb’s family, we have expanded our name.”

Warrick’s career began as a bicycle messenger after he graduated from high school. He delivered messages pertaining to the business of the telephone company, explained his wife, Cecelia, 89, who is an Aljoya House resident.

Warrick worked for the same company as his father and brothers, Don and Bob: Pacific Telephone and Telegraph. When he retired, he was the assistant vice president of Special Services and Engineering.

With the advent of two modernization projects to scrap electromechanical switching systems and install new electronic switching equipment, Warrick recognized the need to preserve the vintage equipment. The museum’s collections are divided into switching, telephones, UNIX (a Bell Labs operating system), outside plant, and other equipment.

“They were going to throw away all of the materials that they had, and he felt that they had to be preserved. He was high enough up that he was able to make that happen,” Cecelia said.

The couple met at a ballet in Seattle.

“We both had lost our mates many years before,” Cecelia said. They started dating and then got married.

“We were just happy with each other,” she said. The couple was married for nine years before Warrick’s death.

Working as a telephone operator was Cecelia’s first job, long before she met her husband. She enjoys the switchboard at the museum, she said — it is what she once did.

Perhaps the only foreign relic is the British post office call box model K-6 dating back to 1936. It is from Norwich, England. A museum volunteer had a contact in England over shortwave radio and discussed getting a call box for the museum. British Telecom provided the call box, and the British Air Force arranged for the call box to be shipped out on a Russian cargo plane to Boeing Field. Boeing then transported the 1,500-pound box to the museum, where it was hoisted up to the second floor.

“You can’t just walk through in five minutes,” Cecelia said.

A collection of early telephones at the museum dates back to the late 1800s and early 1900s (Museum of Communications/Contributed photo).

This crossbar office is an electromechanical switch from 1937. This frame tests other frame circuits through relays. Switching equipment in the central office connects telephones and routes calls, and six operational vintage panels are displayed at the museum (contributed photo).