Islander’s naval service earns him a map honor

By Rebecca Mar

Mercer Island Reporter

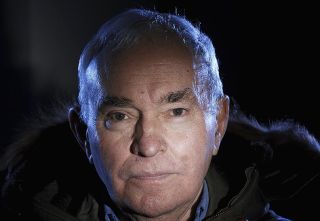

Imagine your name was a place on the world map, and you didn’t know. Retired Navy Commander David Beyl’s name has been on a map for 30 years. He didn’t find out until this past Thanksgiving. The place: Beyl Head, a promontory on Antarctica’s southwestern coast, just a mere thousand miles or so from the South Pole.

Beyl’s nephew, Jerry Beyl, discovered Beyl Head while researching the Beyl family on the Internet.

In the mid-1970s, Cmdr. Beyl was assigned to McMurdo Station, Antarctica, where he oversaw the Navy’s recovery effort for two of three military aircraft that crashed, quite literally, at the “end of the earth” — a remote, icy location known as Dome Charlie, Circe and “C.”

Beyl Head commemorates its namesake’s success in recovering the downed planes: valuable, versatile, mammoth LC-130 Hercules transports. The LC-130s were then still relatively new to the ranks of military aircraft.

In 1975, recovering and repairing the huge planes was a complex and dangerous mission.

“I’d never done anything quite like it before,” said Beyl of his mission. “That was an epic in naval aviation.”

The planes crashed in 1975 while flying a support operation for the French base at Dome Charlie. Miraculously, nobody was killed.

The huge transport planes, still in use today, can hold over 20 tons of cargo and 9,000 gallons of fuel, and are equipped with ski landing gear. The skis alone weigh 2,000 pounds each and measure 20 feet long by 6 feet wide.

The first order of business was to build a camp and runway at the treacherous crash site — an ice dome rising nearly 11,000 feet above sea level, the equivalent of Oregon’s Mt. Hood. The crew had to fly in everything they needed for repair work.

“Nobody had undertaken that kind of a task before. I always felt that we were really out on a limb. If we failed, we had everything to lose,” said Beyl.

The mission to recover the aircraft was featured in TIME magazine on Jan. 5, 1976.

“The loss of the three Hercs has had a devastating effect,” TIME revealed. “Unwilling to give up on the planes, the Navy hopes to repair at least one of the LC-130s this season and fly it out. It would be a remarkable feat — and an Antarctic first.”

The mission was an important one for the Navy. McMurdo had been allotted only five LC-130s, crucial for search and rescue efforts and supplying inland bases. The crew had six weeks to work before the Antarctic winter set in and they would have to leave.

“Winter is two things: extremely cold and dark,” Beyl explained. They could only stay during austral summers, October through February.

After the weeks of furious activity, the crew flew the first plane out in early 1976, but the second plane remained almost another 12 months until flying off the dome on Christmas Eve, 1976.

The Navy honored the efforts of its Antarctic crew.

A U.S. senator read a commendation in Congress to honor the crew’s accomplishments. Beyl received a Navy Commendation Medal, and Antarctic Service Medals were given to the crew.

Beyl’s captain submitted Beyl’s name to the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names (ACAN) of the U.S. Board on Geographic Names (USBGN) for consideration, along with five other names chosen by Beyl. There was no guarantee that the USBGN, a branch of the U.S. Geological Survey, would pick any of the names, let alone in a timely manner. Thus, Beyl held no expectations. USBGN/ACAN is still accepting proposals for Antarctic place names.

Beyl served during three Operation Deep Freeze seasons in Antarctica, 1975-1977, as the third ranking officer and director of operations on the Antarctic Support Force staff at McMurdo Station, an estimated 800 miles from the South Pole. McMurdo, on the southern Antarctic coast, is one of the continent’s few places with open water and access to harbor.

The National Science Foundation financed all activities and even paid Beyl’s salary, Beyl said.

All Antarctic operations have always been science-oriented. In the 1970s, scientists focused mainly on drilling into ice caps, sea ice and the land mass with drill rigs. The ice was more than 100 feet deep in places. Scientists succeeded in extracting minerals, as well as finding fossil fuels and six new animal species in the sea.

Military operations have never been allowed per the Antarctic Treaty, which is renewed every five years to ensure that the continent remains a “natural reserve, devoted to peace and science.” America was one of 12 nations that first signed the treaty, established in 1961. Thirty-four other countries have since joined the treaty.

The U.S. Navy first became involved in Antarctic exploration in 1956 and was later joined by the U.S. Coast Guard and Air Force.

Beyl enlisted in the Navy out of Clear Lake, Wis., where he grew up. He was born in Osceola, Wis., in 1934.

During his naval career, 1954-1978, he served on non-combat duty as a patrol plane pilot, ship’s gunnery officer and flight instructor. He served throughout the United States and in Italy, Japan and Alaska. He also patrolled the Mediterranean Sea on NATO assignment and transported men and equipment to Vietnam during the Vietnam War. During the Cold War, he was part of the North American Air Defense Command, ready to respond to missile threats from Soviet submarines.

After Beyl’s final flight as a pilot in June 1978, he logged in a total of 6,200 career flight hours.

Beyl and his wife of 50 years, Sandra, have lived on Mercer Island since 1980. They have three adult children and four grandchildren.

Despite being retired, Beyl still fixes things. The pilot has owned a custom woodworking business, “Common Sense Woodwork,” since 1984, for furniture and cabinet repair and restoration. He still enjoys trips around the country and abroad, as he and his wife travel with the Elderhostel program.