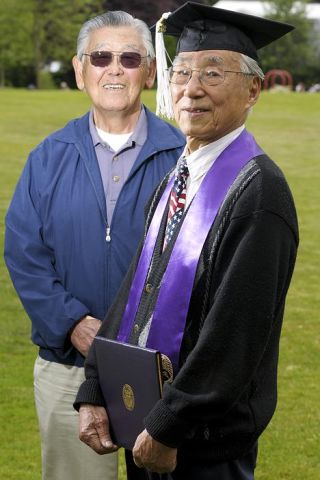

Islander gets diploma 66 years after internment camp detention

By Nancy Hilliard

Mercer Island Reporter

Two Mercer Island octogenarians are celebrating unexpected graduations this season — 66 years after the moment in history that dashed their college careers and sent 120,000 people of Japanese descent to internment camps in 1942.

Among the 14,400 Japanese-Americans from Washington state was Hiromi Nishimura, then a University of Washington student; and of the 3,500 from Oregon was Jack Nomi, who attended Oregon State University.

Their former universities have granted them and other Nisei students of the 1940s honorary degrees “to do the right thing” in face of the great wrong done to them earlier, said OSU President Edward Ray. He will confer Nomi’s degree on June 15, along with 42 others. Nishimura received his honorary degree on May 18 at the UW’s “Long Journey Home” ceremony honoring 440.

Secretary of Transportation Norman Mineta, the keynoter at UW’s Nisei ceremony and a WWII internee, told the 100 or so “late graduates” that “it’s never too late to rejoice that the right thing has been done.” The majority of UW’s 440 Japanese-American students from the ’40s are deceased, including Mercer Island’s Haruo Kato and Ben Ugeno. Among the event’s many planners and sponsors were Tets Kashima, William and Beth Kawahara and Julie Ogata, also from Mercer Island.

“We should use the memory of this unconscionable chapter of our history to strengthen our resolve to stand up for each and every member of our community when we are tested, as we surely will be in the future,” said Dr. Ray.

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Nishimura, in Seattle, and Nomi, in Oregon, had to quit college and pull up roots. Their families had to liquidate possessions and businesses within a month of President Franklin Roosevelt’s evacuation orders. Nishimura’s father, Hisao, had to sell his Seattle apartments, just as Nomi’s family had to “sell for a pittance” its restaurant and farm equipment.

Most locals went to Camp Harmony in Puyallup, Camp Minidoka in Idaho or, as Nomi did, to a livestock pavilion in Portland. For diversion, he and his fellow “inmates” played lots of baseball after clearing the center of animal waste, while guards with machine guns watched in the towers.

Instead of being interned, Nishimura was inducted into military service — a mixed blessing, he said. “It was traumatic to worry about my parents and brother and be separated from them as they went to an armed camp in Hunt, Idaho. Those who went as a family could suffer together.”

By enlisting in the Army, as did 68 other fellow UW Nisei students, Nishimura eventually joined the Army’s Military Intelligence Service with 6,000 Japanese-Americans who interrogated POWs, did translations and radio interceptions. While in Burma, he contracted malaria. He served the United States from 1942-46.

Although Nomi was not called into military service for medical reasons, he eventually became part of the team that oversaw Boeing’s airplane sales to Japan, until his retirement in 1990.

The pieces of paper given to Nishimura on May 18 and Nomi on June 15 are not what is meaningful, they say. Both already have completed their educations — Nomi in engineering at the Missouri School of Mines, and Nishimura in biology at UW. Nomi worked for Boeing for 35 years, and Nishimura was on the UW faculty in physiology and biochemistry for 25 years. Both have resided on Mercer Island for more than three decades.

Instead, the honorary graduates consider this a “teaching moment.”

“We are Americans first, and of Japanese heritage second,” said Nishimura, wearing a stars and stripes tie and carrying his Veterans of Foreign Wars card. He manages the VFW Hall on Mercer Island.

“I am not bitter, but full of gratitude at this benevolent gift of righteousness that my university has given us,” he added. “My hope is that recognizing this injustice shows we can’t judge [loyalties] by looks or heritage.” Nishimura cites recent violations of Arab or Muslim civil rights in America as dangerously close to repeating that wartime mistake.

“My wife, Dorothy Hoshida Nishimura, and I tell our offspring the story of our parents’ struggles, and that we cannot take for granted our good lives today.” The Nishimuras have three daughters, Celia Sekijima, of Issaquah, Karen, who works in Palo Alto, and Robin, who lives at their Mercer Island home. For his descendants, he has written a book, “Trials and Triumphs of Nikkei.”

Nomi’s wife, Tamaye; his daughter Julie Arzenti, in a Boston suburb; sons, Russell, of Sammamish, Jeffrey, of Issaquah, and other relatives will attend the Corvallis event on June 15 “to show appreciation.”

“Hopefully, this [honorary graduation] will let others know about the evacuation movement of our history, so we don’t repeat it ever again,” said Nomi.