The beginning of the Mercer Island cougar craze began on Aug. 5 when a photo of a cougar captured on surveillance the night before made the rounds online.

Since then, the police department has had a lot of public engagement with regard to the cougar sighting, Commander Jeff Magnan with Mercer Island PD told city council on Sept. 3.

He was joined by police Chief Ed Holmes, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Sgt. Kim Chandler and research scientist Brian Kertson, for a combined presentation on how the agencies responded to reports.

Magnan said police took advice from Fish and Wildlife on how to address the cougar. They looked for signs of the cougar at the scene, physical evidence of paw prints, or anything that could lend to the validity that the animal had been there.

If police saw the animal, they were advised to chase it up a tree, until it could be moved to a more suitable location, Magnan said. And when a timely report came in, the police response had been the same.

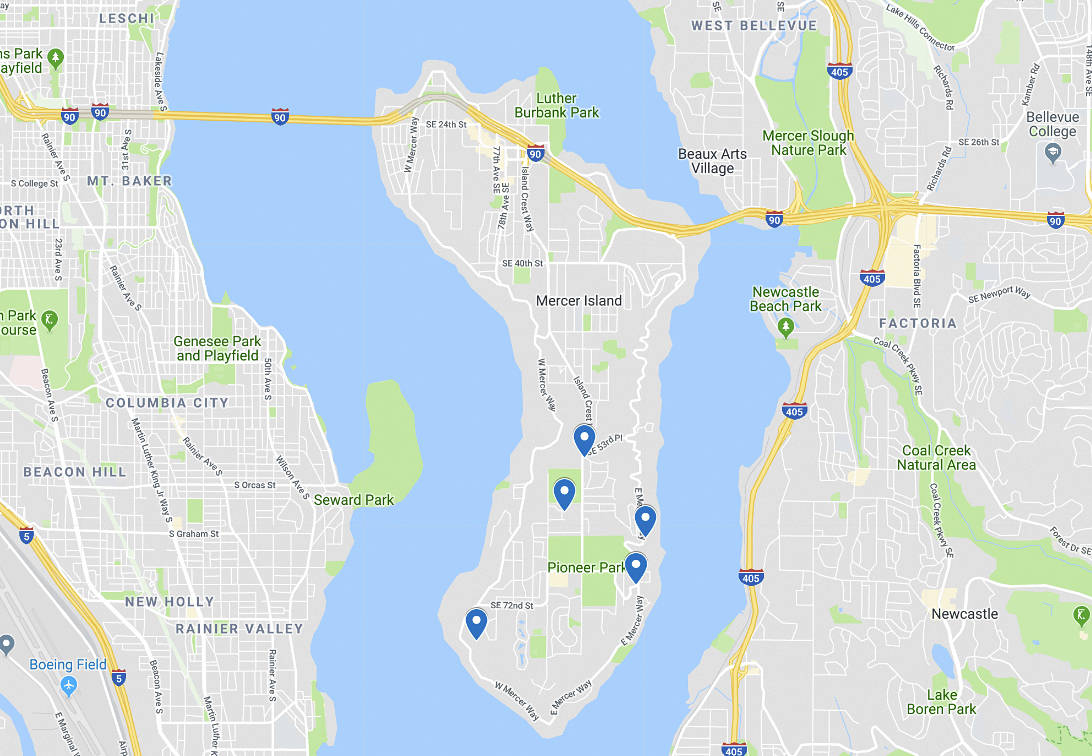

But there were only two confirmed sightings that came in out of the 29 calls of service regarding the cougar. The total number includes three possible sightings and 17 unconfirmed reports, and seven citizen calls were requesting an update on the cougar situation.

“In law enforcement we can only prove what we can see and act upon,” Magnan said. “It’s not what we know but what we can prove.”

Magnan said when a confirmed or possible sighting came in, Fish and Wildlife were called to the scene to help. When Fish and Wildlife responded, they helped search for tracks in certain cases and provided their expertise.

Kertson, carnivore research scientist with Fish and Wildlife, has focused much of his research of 20 years on cougars — specifically, on cougars in the “wildland urban landscape.” He had a decade-long research project — in the Cascade mountains, in the western slopes around North Bend and Fall City — examining cougar behavior when they end up in residential areas.

He was there to distill any fears residents may have on the animal, he said.

“The fact that they’re highly adaptable and far ranging combined with the fact that they are the second-largest cat in the Western Hemisphere is basically why we find ourselves where we are tonight,” Kertson said. “It naturally elicits a fear response in people.”

Cougars, as apex predators, make their living looking for prey to catch, kill and consume. And while capable to kill the largest prey relative to any other cat in the world — killing animals five to six times larger than themselves — it’s primarily deer and elk that make up the bulk of the cougar diet.

But they’ll kill things as small as rabbits and rodents. Even though the Island is home to many small creatures, Kertson said it’s not suitable for cougars.

“It’s far too small. It’s far too urbanized,” he said. “However, cougars are highly adaptable and probably enough suitable habitat on the island and deer to support a cougar for a very short duration. Exactly how long that is, it’s tough to say.”

He said the situation would depend on how tolerant of people that particular cougar is. But he wouldn’t expect the cougar to expend any significant amount of time on the Island. When comparing the size of the Island to a typical male cougar’s home range, the city falls short.

In sharing more on the animal, Kertson outlined the four types of encounters people have with cougars: sightings, encounters, depredation and actual attacks. But since 1890, there have only been 21 cougar attacks on humans and of these, only two have been fatal.

“We’ve heard a lot from the public, from people concerned about … ‘I can’t go running anymore. What about my kids walking to school. What about my ability to ride a bike or garden,’” Kertson said. “And I think for the most part, it’s important for people to recognize that they are in fact very safe.”

When asked by the city council if the cougar was still on the Island, Kertson said it was likely the mountain lion had been “gone for some time” and that in his experience, cougars who make their way to very urban settings like Mercer Island, don’t tend to stay long.

“After doing a walkabout on the island and sizing it up as not being what he’s looking for, he likely went back,” he said.