With general election ballots arriving in King County mailboxes this week, it’s time for local voters to study up on the two measures being out before them.

Ballots should arrive by this Friday, and must be mailed back or dropped off in an official ballot box by Nov. 8.

Here’s a short guide to the two King County-wide proposals being put to a vote:

EVEN NUMBER ELECTION YEARS

Tired of feeling like you’ve got a ballot to fill out almost every season? Then you may want to consider approving Charter Amendment No. 1, which will change when county representatives have their elections.

National elections always take place on even-numbered years, but King County has elections for its executive, council members, assessor, and elections director on odd years. Approving the amendment would change that and limit the number of times you vote.

If this amendment passes, the assessor, elections director, and council members representing districts 2, 4, 6, and 8 will be held in 2026, rather than 2025. The county executive and remaining council members would have their election scheduled for 2028, rather than 2027.

This means that those elected in 2023 (consisting of the former group mentioned above) and 2025 (the latter), the last odd elections for the county, would serve only three terms before being up for election again. Four-year terms would resume after the even elections.

Beyond potentially reducing voter fatigue, the county hopes to increase voter turnout, as participation in even elections is always higher than odd elections; even elections are also more diverse than odd elections.

There is no official opposition to this amendment.

The county already elections its prosecuting attorney and superior court judges during even elections.

Washington state legislators introduced a bill (HB 2529) in the 2019-2020 session to change all local jurisdiction elections to even years in 2020, but it did not leave its committee.

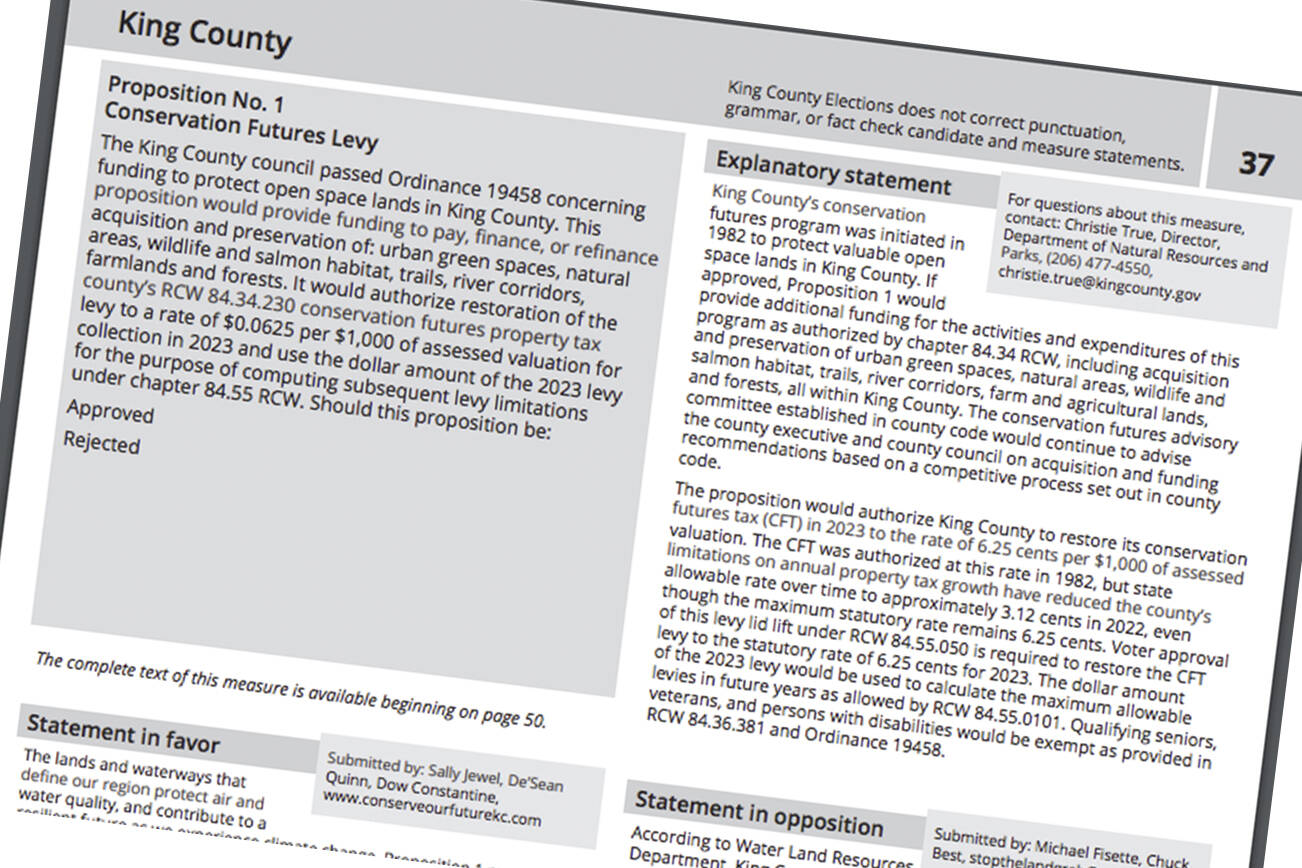

CONSERVATION FUTURES LEVY

Unlike the proposed charter amendment, Proposition No. 1, the Conservation Futures Levy, is likely to garner opposition.

The levy is not a new tax; King County implemented this levy more than 40 years ago, but this is the first time it’s back on the ballot, asking voters to reset the levy rate to its maximum of 6.25 cents.

The levy collects property taxes to fund King County’s Land Conservation Initiative, which gives the county funds to buy open spaces — urban green spaces, natural areas, wildlife and salmon habitat, trails, river corridors, farm and agricultural lands, and forests — to preserve and protect them from development.

Also a part of the Land Conservation Initiative is King County’s Farmland Preservation Program, which has bought up the development rights of farms around Enumclaw, for example, to protect them from development. The FPP uses funds from collected through the Conservation Futures Levy.

Currently, the levy rate is at 3 cents per $1,000 in assessed property value. It’s shrunk since the levy was first implemented because state law says jurisdictions can only collect 1% more in revenue from property taxes over the previous year, so when property values increase at a faster rate, the tax rate must decrease to compensate. Resetting the levy rate to its maximum is officially called a “levy lid lift.”

At 3 cents, median property owners ($694,000 in property value) see an annual tax bill of about $21; doubling the tax rate would bring the annual tax bill to just over $43.

Although taxes from the levy are used to acquire control of open spaces, the Land Conservation Initiative doesn’t tackle these projects alone — cities, farmers, businesses, and nonprofits need to partner with the county and are usually required to pony up 50% of the necessary funds before the program purchases land. (There are exceptions where the match is waived.)

Proponents of the levy claim the Conservation Futures Program needs the additional funding to protect vulnerable land from climate change; conserve trails, natural lands, and forests for future generations; and retain farmland for local food production.

Opponents argue that the county already controls extensive swaths of unincorporated land, but doesn’t have the resources to maintain all of it. Additionally, preventing development in the county means higher property taxes for everyone, since fewer people will have the opportunity to move into King County to spread out the tax burden.

FACT CHECKING

The official opposing statement against the levy claims King County already controls nearly two-thirds of the land inside the county.

“According to Water Land Resources Department, King County already controls/owns 61.2% of the land in King County! That’s right, government already controls almost two-thirds of the land, yet they want more,” wrote Michael Fisette and Chuck Best. “Open space is important, but enough is enough. At 61.2% and growing, King County passed the balanced percentage a long time ago.”

This is wildly inaccurate, though Fisette corrected his statement in an email interview saying that government entities — from cities to the feds — control 61.2% of King County land.

King County itself only controls about 3%, roughly 42,000 acres, of land, which is mostly rural residential and agricultural areas.

The federal government controls nearly 26%, mostly of forests.

Cities control about 11% of county land, which is mostly urban areas and forests.