As the city of Mercer Island’s Development Services Group and Planning Commission continue their work on the residential code update, property rights advocates feel like their voices are being lost in the discussion.

Framed as a way to address “concerns regarding residential development and the rapidly changing character of Mercer Island’s neighborhoods,” the debate has centered on ways to limit the size of new homes.

The code update process was kickstarted when Councilmember Dan Grausz proposed a moratorium on residential development, hitting a nerve in the community. The moratorium was not approved by the council majority, but it started a conversation on what the city can do to preserve the look and feel of its neighborhoods from the teardown trend hitting the greater Seattle area.

The city has heard from some citizens that “new homes are out of scale and incompatible with neighboring homes, “new homes are too close to their neighbors” and “too many trees are coming down,” according to a presentation at a Jan. 11 public meeting hosted by the Planning Commission.

The commission will host another community meeting from 9:30-11:30 a.m. this Saturday, Feb. 25, at West Mercer Elementary to explain the current code and get public input on the proposed revisions.

But some residents want to be able to weigh in on the changes, which they say will affect their property values, on a much larger scale: an Island-wide vote.

The Reporter organized a meeting with realtors, brokers and residents at the Mercer Island Library on Feb. 14 to get their take. Many felt that the changes are a constraint on property rights, and would like the commission to provide an option to leave the code as is when it presents its recommendations to the City Council.

“Every single one of these revisions affects size,” Allen Hovsepian, a managing broker with Windermere Mercer Island, told the Reporter. “It comes down to property rights. This will affect real people who have real rights attached to their property. If the city is going to do this, they should let us vote on it.”

The public comments available on the city website are split in two camps: those who value “neighborhood character,” housing diversity and more restrictive guidelines for new homes, and those who want “to use their property as they wish.”

Some proposed revisions are likely to find common ground, including adopting tree protection regulations, reducing construction hours and eliminating impervious surface deviations.

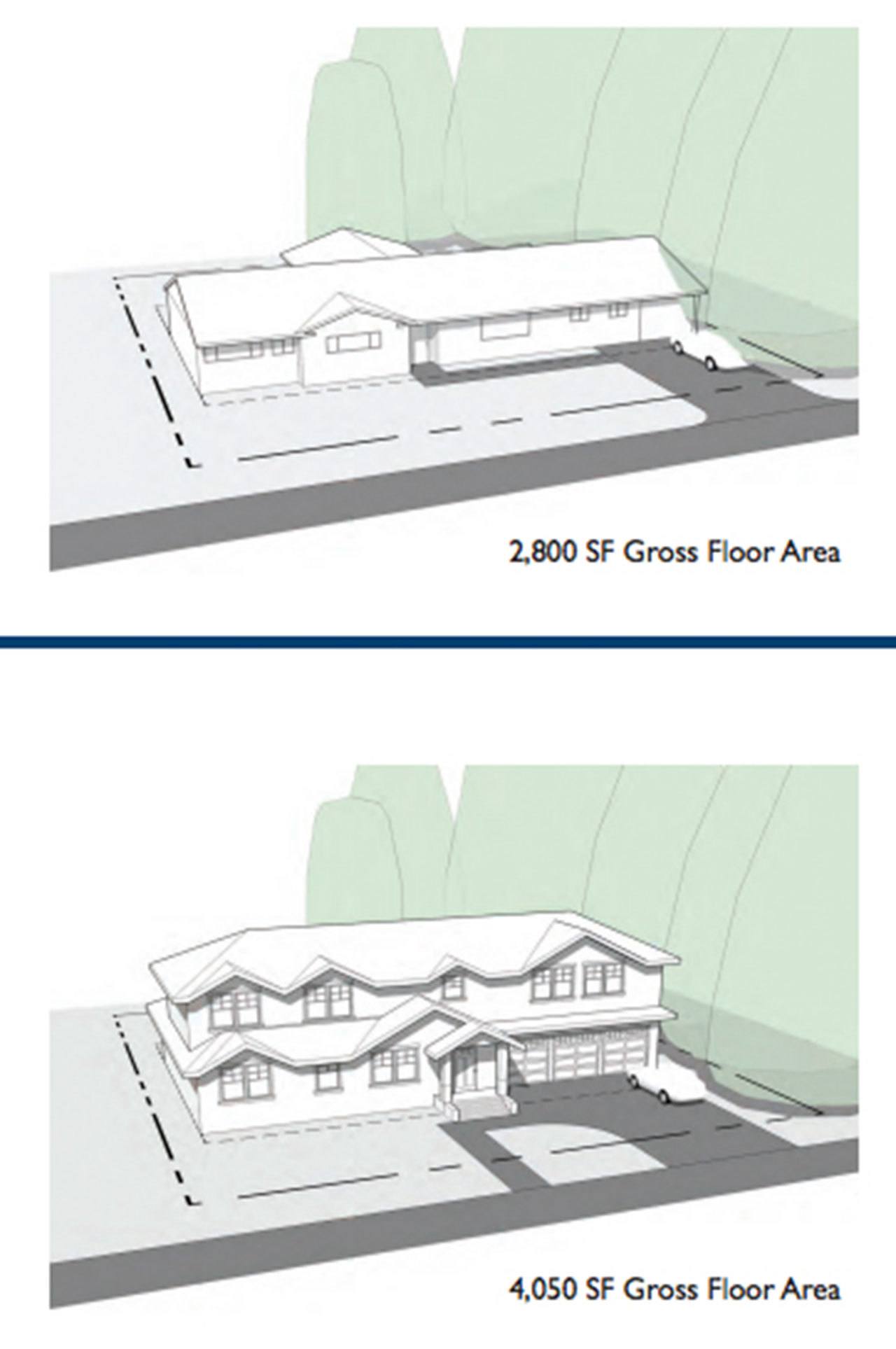

Those in the latter camp feel that the other proposed changes, which include adopting a ”daylight plane” setback that limits the upper floor massing, adjusting the current maximum gross floor area from 0.45 down to 0.40, providing a maximum house size of 4,000 square feet, increasing the required setbacks between houses, limiting the height and size of accessory dwelling structures, don’t reflect their views.

Other realtors and residents told the Reporter that the current code would work fine if it was enforced; the real problem is the “rubber stamping” of variances by the city’s DSG staff. The DSG department is primarily funded by development permit fees.

The city recognizes that its “development regulations help to set the price for land.”

“If we limit the size of homes that can be built, it will effectively reduce the price that a developer is willing to pay for land in Mercer Island,” according to the Jan. 11 agenda. “How important is it to protect property value for resident’s that need to ‘cash out’ their property for retirement?”

The perceived problem, described by the city as the “rapidly changing character” of Island neighborhoods, is due to the quick rebound of the building industry after the recession, and job growth in the Seattle area, Hovsepian said.

People moving to the Island now are looking for different things than they did 50 years ago; not for galley kitchens and car ports, but for his and her walk-in closets, four or more bedrooms, higher ceilings and even a home gym, theater or dual master bedrooms. Those elements are not possible with the smaller footprints that would result from the code revisions, he said.

At the Jan. 11 meeting, the Planning Commission asked if the goal of the update should be retaining traditional scale, or if the city should recognize and allow for the fact that over the decades, people have sought more space in their homes. The average Mercer Island single family home was 3,300 square feet in 1960, and is 4,675 square feet today.

Hovsepian said that the proposed changes have not been weighed in on by enough Islanders, but are being pushed by a small, vocal group. Supporters of the proposed changes, who sent out a petition in January 2016 that received 175 signatures, say that “the concern regarding loss of neighborhood character, overly large houses, and loss of trees is widespread on Mercer Island.”

Grausz lives in the First Hill neighborhood of Mercer Island, which he has described as a “war zone” under constant construction. Other neighborhoods in Mercer Island have experienced waves of new development over the years.

Hovsepian grew up in Mercer Island, and said that when he drives around the community, he feels that not much has changed. Some of his childhood friends’ houses have been torn down, but that’s the price of progress and a free market, he said.

Over the next few months, the Planning Commission will review concepts and citizen comments, and will make a recommendation on residential issues to the City Council in Spring 2017.

To share your thoughts, email residential@mercergov.org.

For the Mercer Island City Council’s Feb. 21 agenda bill on the residential code update, click here.