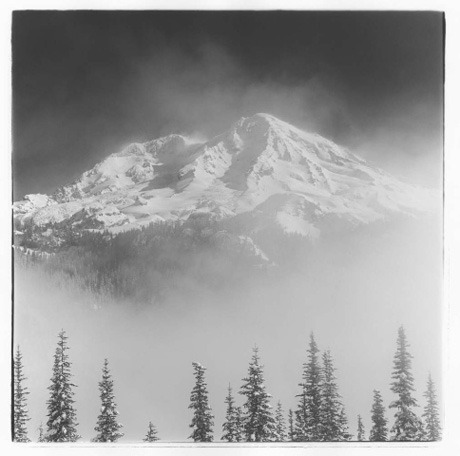

There must be millions of images of the iconic Mt. Rainier. What is there that is new to see? Plenty.

A new book by Islander photographer Fred Milkie Jr. entitled “Alone Around the Mountain: A Visual Memoir” takes a very personal look at the peak. The black and white images inside reveal that the mountain is far more than the snowy alp we see from afar and think we know by heart. It is an intimate view shaped by a lifetime on its slopes, glaciers and forests.

Milkie has brought to life the varied views and moods of the mountain that shaped his family and his life’s work. His tools? A pair of old snowshoes and a black and white film camera.

The son of a highly-regarded commercial photographer, Milkie is a similarly skilled and artistic photographer who graduated from Mercer Island High School in 1968. He and his wife, Renee, who have two grown children, still live here.

His father, Fred Milkie Sr., was a successful and talented commercial photographer who was also the official photographer of the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair. Photographs by the elder Milkie, who died a few years ago, documented the changing culture and look of Seattle and its environs through the middle of the last century.

The book represents a tribute to the fading art of what he considers the truest form of photography: the use of black and white film. The book is an atonement of sorts for Milkie — to honor his father’s memory and make peace with him at last.

For many who came of age in the 1960s, perhaps the most difficult of relationships was those between fathers and sons.

It was a stormy time for Fred Jr. and his father. There was the Vietnam War, changing mores and old-fashioned teenage rebellion. Up to and during those years, Milkie Sr. took his family, which included Fred, his brother Paul and his two sisters, up to the mountain nearly every weekend. They traced the trails and the sites that his father then — and later, they — knew by heart. As the children became teenagers, they wearied of the weekend trips, their attitudes documented in family photos on the mountain.

Born in Seattle, Fred Milkie Sr. was the son of Lebanese immigrants who scrimped and sacrificed to send their son off to college. The dutiful son excelled, finishing a business degree at the University of Washington. But fate intervened. Not long after he completed college, an offer came for work that ended up changing the course of his life. He found himself running Paradise Lodge within the Mt. Rainier National Park. He fell under the spell of the wonder and beauty of the mountain. He left his other work and told his undoubtedly confused parents that he was going to become a photographer. His first studio was in the Pike Place Market, then in the basement of the St. Regis Hotel at the corner of Second Avenue and Stewart Street. His professional work documented the swift and startling change that came about in Seattle after World War II into the 1960s and beyond.

Milkie Jr. and his brother, Paul, followed their father into commercial photography, both attending arts school at the University of Washington. They joined their father’s flourishing studio in Seattle.

As the years passed, Milkie began to return to the touchstone that was his father’s — the mountain. He began to retrace the routes that his father had led them on so many years ago and that they both knew so well. He began to see more clearly the magic and meaning it held for his father. And after years of taking pictures of frozen food and the like, Milkie wanted “to be a photographer again.” Practicing his craft in solitude on his father’s mountain provided the perfect avenue.

To understand the physical undertaking of the book, one must reconcile the idea of a single person on a pair of aging $99 MSR snowshoes circumnavigating the giant volcano with a pack and a camera — over and over again.

Milkie figures he started taking photos for the book sometime in 1995 or 1996 and finished late last year. He has thousands of images. Many of these trips took place in the winter. He would begin at daybreak and walk up to 18 miles.

“Most of my trips were day trips,” he wrote in an e-mail. “I’d sleep in the back of my car and start early in the morning.”

He made things difficult for himself. He wanted a balanced set of views from around the peak. As such, he had to make sure that each side of the mountain, and each view, was included. That balance required dozens of extra trips. Nearly all were done alone.

He wants to make the point that the photos are not alerted or changed in any way. The prints reflect exactly what Milkie saw and photographed with his equipment on the mountain. The variables involved were only the use of a particular lens, a filter perhaps and ambient light. The photos in the book are not cropped. Instead, they are printed with a black edge showing the frame of the negative, he said.

Each has the name of the place — from “The Grove of the Patriarchs,” to the “Ipsut Pass Trail” to a view named “Puyallup Cleaver from Aurora Lake.” Names and views no doubt he learned from his father.

It has been a bittersweet journey.

The brothers are letting go of the studio where they have practically spent all their lives. Photography has changed, Milkie says simply.

Their father built the studio in 1962 when Milkie was 7. It is very much reminiscent of the time and includes a curved interior glass-brick wall and a deco concrete frieze adjacent to the front door.

It was once a busy place.

There is a huge high-ceilinged studio space in the rear of the building with a full kitchen, where photos were taken of frozen pies and dinners and other products for advertisements. There were darkrooms and offices, drawers that held hundreds of contact sheets and thousands of negatives. But it is no longer needed. It is up for lease. Nearly all of the shoots that Milkie and his brother, Paul, do for clients are done on location.

There are no takers for the space as of yet. Most of the equipment and furnishings are gone. There are a couple of drawers with family photos still waiting to be sorted and dispersed. The thousands of negatives and prints of his father’s were contributed a few years ago to the Museum of History and Industry. But there is no hurry. The brothers have as much work as they want. Other properties owned by the family along the block, just off busy Olive Way, only a few blocks from downtown, are all rented out.

As with similar endeavors, many hands made the project complete. The writing, Milkie said, was a challenge for him. He wrote out what he wanted and gave it to his writer friends and fellow Islander grads, Greg and Kathy Palmer. He said they “put it all in order.” Another friend and collaborator, Terri Nakamura, did the design, and sister Melanie made the maps “of his wanderings” and encouraged him in the project.

Milkie is considering another book. There are one or two that are waiting to be done, he said. But instead of on foot, it will likely be on his bike, which he rides back and forth from Mercer Island to Capitol Hill every day, rain or shine.

On his back there will be a camera with film.