After nearly six years of being known as Mercer Island John Doe 2018, a deceased man has been publicly identified as Angel Arroyo Hernandez.

Mercer Island Police Department (MIPD) investigators teamed up with the DNA Doe Project for the last three years and engaged in meticulous forensic research to give a name to the 53-year-old drowning victim, who was wearing only black socks when he was located floating off the shore in Lake Washington on the south end of Mercer Island on May 6, 2018.

The DNA Doe Project confirmed his name on Feb. 16 of this year in a press release. The case was actually solved in May of 2022 when the project’s team members connected with the man’s daughter residing in California and verified the identification, according to project team leader Trish Hurtubise and MIPD public information officer Lindsey Tusing.

Hurtubise explained the lengthy gap between the solve and the press release: “Any publication of it or notification to the public, that is entirely up to the agency involved as well as the family. We just follow their lead and they’re told when a release will come out.”

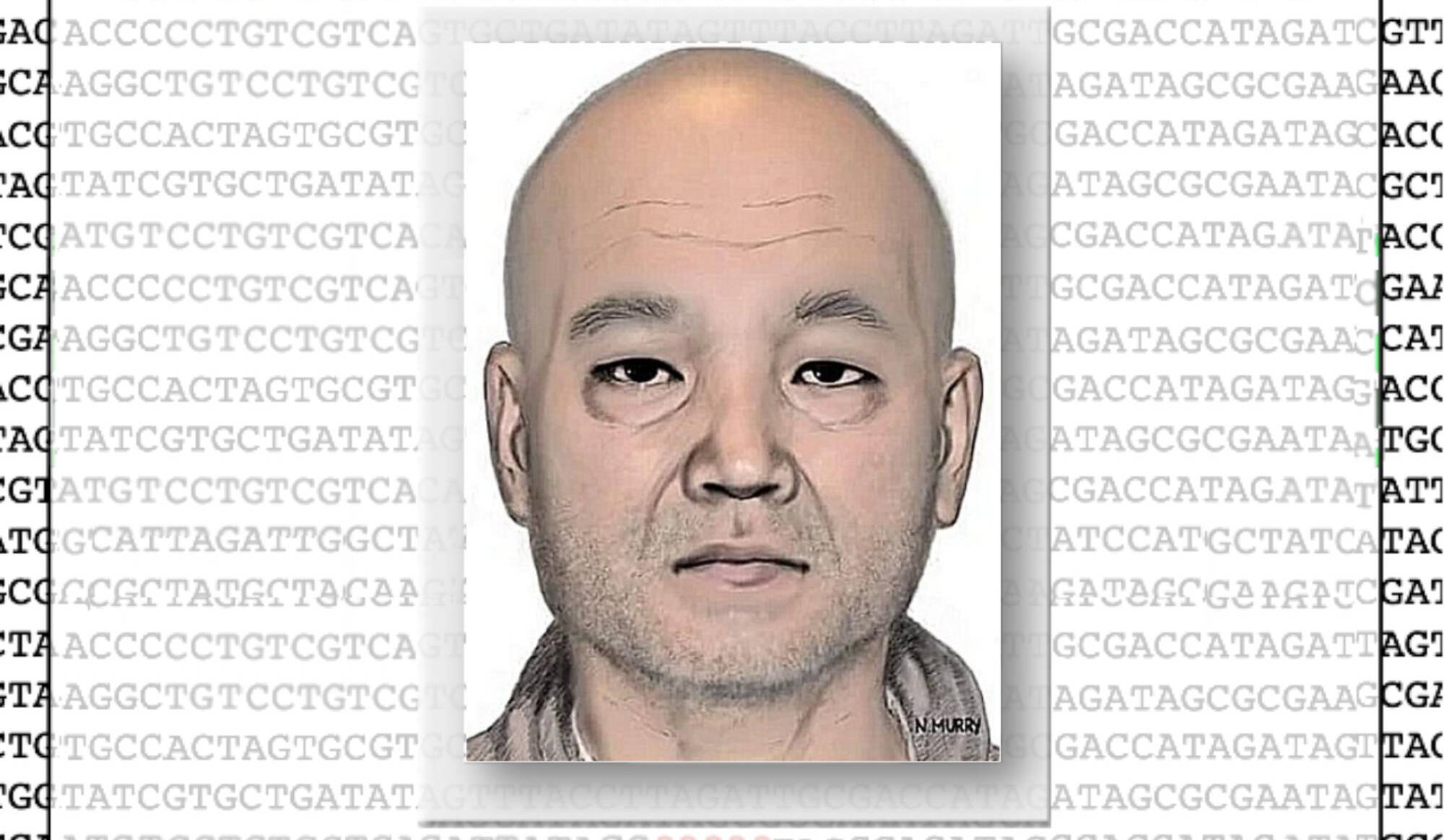

Hernandez was 5-foot-4, approximately 120 pounds and was said to have been estranged from his family for some time before his death, according to the project’s site. Authorities initially noted that the man was possibly of Asian descent and believed he could have been deceased for a number of weeks before the discovery.

On what prompted MIPD investigators to reach out to the DNA Doe Project for assistance in identifying the man, Tusing noted: “When MIPD took custody of the deceased, he had been in the lake for weeks. He no longer had distinguishing physical features that would make identification possible on appearance alone. Our detectives collected DNA samples from the deceased and sent those to the Washington State Patrol crime lab. They ran the samples through their databases and could not find a match, only that the tissue belonged to a human male.”

Retired MIPD detective sergeant Jim Robarge was the local lead on the case, which the department brought to the DNA Doe Project in mid-2021 for an attempt at investigative genetic genealogy. After creating a DNA profile from a blood sample and uploading it to a pair of public databases, thousands of matches arose — but none linked up with the man’s close relatives.

While delving into the closest matches, the volunteer genealogists learned that the man was Hispanic since many of his ancestors hailed from Mexico and the southwest United States. Throughout the process — which included sifting through historical records hand-written in Spanish — they traced his family across 11 generations and more than 200 years to land on Hernandez’s identity. While evaluating the small matches and patterns between them, they eventually located the daughter, according to Hurtubise, who added that the man was believed to have been living on the Eastside prior to the drowning.

“This case is a good example of why cases of unidentified Hispanic and Indigenous people are so challenging,” said DNA Doe Project team leader Rebecca Somerhalder. “Even though it seems like a lot of matches, when they are all so distant to the Doe, we have a lot of work to do with limited access to records in Central and South American countries to work with.”

Hurtubise encourages people of Hispanic or Indigenous ancestry to upload any type of results to GEDmatch to aid in the project’s research in such cases.

In the Hernandez case, Hurtubise said the project team relayed regular updates to MIPD throughout its robust research. Initially, team leaders communicated with Robarge and then touched base with current detective sergeant Dominic Amici.

Hurtubise recalled that Robarge hoped the case could be resolved before he retired.

“So I said to him, ‘OK, challenge accepted,’” she recounted, adding that about a month and a half later — shortly after Robarge retired — DNA Doe notified MIPD that they had secured a candidate (possible identification) and the process could be nearing fruition.

It was through a coincidental chain of events that Hurtubise came into contact with the man’s daughter.

“I reached out to an individual to say, ‘Hey, could you maybe help us out?’ And she reached back to me and said, I think her words were, ‘I wondered when I would get a call like this.’ And then immediately I felt panic, because it has never happened like that before,” said Hurtubise, who thought she was possibly connecting with a third cousin and not a daughter. (The daughter was not available for an interview for privacy reasons.)

Confirming an identification is always a bittersweet scenario, said Hurtubise, who has been involved with about eight to 10 successful IDs during her five years with the project.

Hurtubise led the Reporter through the emotional process of searching to solving a case: “When you’re doing a search, you have all the energy of more, like, puzzle logic and adrenaline to try and figure something out. And when the immediate moment that you realize that things have been solved, it’s a great feeling, but then you immediately realize that a family is going to be affected by this solve. So it’s kind of a double-edged sword.”

MIPD retired detective sergeant Ryan Parr, who worked with several fellow officers in the early stages of the case, noted in the public comment section of the department’s Facebook page: “That was my case originally and haunted me for a while. Good work identifying him and bringing closure to his family.”

On behalf of the MIPD, Tusing told the Reporter, “We have to give every bit of credit to the investigators at the DNA Doe Project. Their expertise, patience and determination are entirely to thank.”

For further information, visit: https://dnadoeproject.org/case/mercer-island-john-doe-2018/