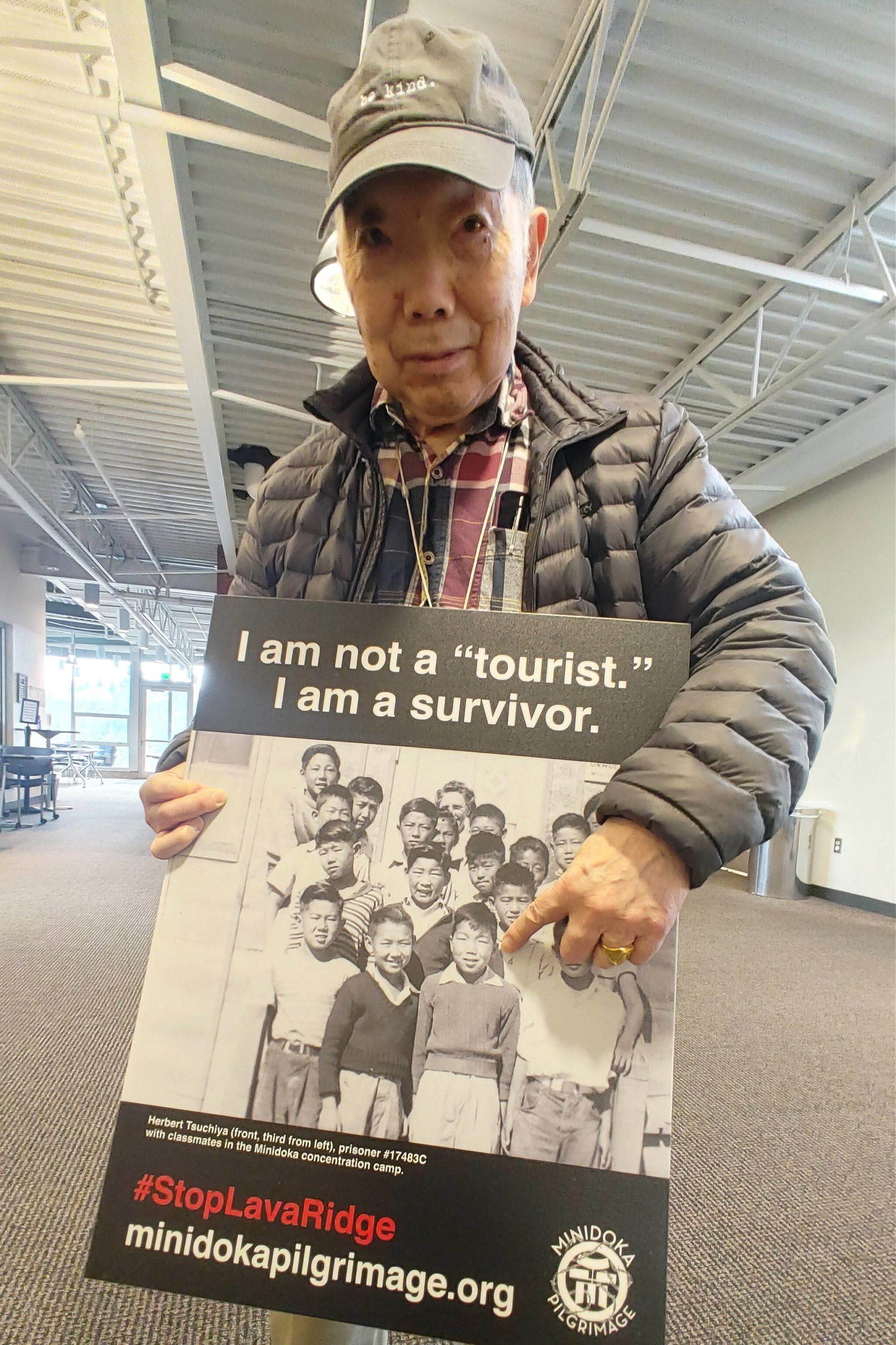

Herbert Tsuchiya glances at a photo of his fifth-grade class emblazoned on a poster and points to where he’s located in the group. He touches the photo briefly and is silent.

Front row, second from the right, age 10. He’s listed as prisoner #17483C at the Minidoka Japanese American internment camp in southern Idaho, where he and family members were incarcerated for three years during World War II.

Tsuchiya is now age 90 and a resident at Aegis Living on Mercer Island, where on March 2 the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Shoshone Field Office sought public comment at the city’s community center on the draft environmental impact statement (EIS) for the proposed Lava Ridge Wind Project both on and near the camp site. The project could involve the placement of a commercial-scale wind energy facility featuring about 400 mammoth turbines covering approximately 84,000 acres of federal, state and private land, according to a press release.

The project doesn’t sit well with Tsuchiya and copious others — survivors, descendants and allies — who attended the open house.

“I think the project is going to negatively impact the historical site of the Minidoka concentration camp,” said Tsuchiya, who said that prisoners not only lived on the land, but tended to it during those three years. “Four of my brothers served in the US military while we were incarcerated in the camp.”

Tsuchiya has traveled to the national historic site three times since the 1940s with the Minidoka Pilgrimage group, which includes planning committee members and local event attendees Marie Okuma Johnston and Kanako Kashima.

As Johnston intently listens in, Tsuchiya noted that he’s grateful to have support from others who also voiced their concerns about the proposed project.

He hopes that through community engagement, “There can be more emphasis placed on the disregard and the challenges that this project impacts our community and our history that we want to preserve for our future generations — so that the same mistakes will not be replicated again for our future group of people,” he said.

Mike Courtney, BLM Twin Falls district manager, said in a press release regarding the Magic Valley Energy-proposed project: “The public’s input at this point in the environmental impact statement process is critical to a thorough analysis — particularly considering such important issues as impacts to Tribes, the Minidoka National Historic Site, greater sage-grouse and livestock grazing.”

According to the web site of Magic Valley Energy, an affiliate of LS Power: “Wind energy is an excellent investment in regions sensitive to water supply constraints. These facilities can be constructed and operated sustainably for the long term without concerns that further drought conditions will threaten their ability to provide jobs and contribute to the local economy.”

Heather Tiel-Nelson, BLM Twin Falls District public affairs specialist, said that the nearly 1,000-megawatt proposed project is located 25 miles northeast of Twin Falls and if it is built could power 350,000 homes.

BLM has received nearly 2,500 responses that helped it shape the alternatives within the 1,800-page draft EIS. Tiel-Nelson said they will read every comment that is sent their way, and those concerns will play a role in further refining the analysis and hopefully reducing the impacts from the massive and viable project that can produce renewable energy.

In the EIS, preferred alternatives C and E moved the turbines a significant distance away from the Minidoka site.

“We heard a lot from the Japanese American community who are keenly interested and the potential impacts to the Minidoka National Historic Site. It became really important for us to bring our public open house to Portland and Seattle to give folks an opportunity to ask questions and talk to our specialist who helped to create the draft environmental impact statement,” said Tiel-Nelson, adding that the Mercer Island Community and Event Center was suggested by the National Park Service as a convenient location for people to gather for the four-hour open house.

More than 13,000 Japanese Americans were imprisoned at the Minidoka War Relocation Center as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066 after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Ten internment camps existed in the United States from 1942-45.

On Feb. 19, President Joe Biden announced on the 81st commemoration of the signing of Executive Order 9066 in a White House statement: “We reaffirm the Federal Government’s formal apology to Japanese Americans for the suffering inflicted by these policies. And we commit to Nidoto Nai Yoni — to “Let It Not Happen Again.”

Mercer Island resident Johnston, who is a first-generation Japanese American, feels that the proposed project will alter the physical and emotional environment of the site. Her family doesn’t have any direct connection to Minidoka, but she’s driven to speak out to preserve the survivors’ legacy and recognize the immense effort they put into living in a remote and desolate area.

Regarding Biden’s statement on the Day of Remembrance of Japanese American Incarceration, Johnston noted: “How are we going to remember when we’re disrupting the place where the camps once were? This could be another dark moment for American government if it happens.”

Kashima, also a Mercer Island resident, said her grandfather was incarcerated at Minidoka and added that the camp is a sacred site that shouldn’t be disturbed.

“People say, ‘Oh, you’re just tourists’ or whatever, but it’s not that. It’s that we are descendants, we have memories. Although I was born after the war, what my grandfather went through is still very, very emotional for me,” she said.

Proposing to place the wind turbines at the site is like a “slap in the face” to the survivors’ descendants who travel to Minidoka, she added.

Fellow Islander Toni Okada, who had family members incarcerated at Tule Lake in California and Heart Mountain in Wyoming, said she hopes that the BLM will listen to the public and locate the wind farm elsewhere.

“People need to learn about them and feel, kind of experience second hand what the people in 1942 went through,” she said of the camp sites. “It would be very difficult to experience that kind of depth of emotion if there are big wind (turbines) very close to the site.”

To download the draft EIS, visit: https://bit.ly/3EirzxD