Filmmaker Andy Schocken will be in attendance as the Stroum Jewish Community Center (SJCC) and Seattle South Asian Film Festival present his film “Song of Lahore” on Oct. 19.

Schocken, who grew up in Mercer Island and lives in New York, co-directed “Song of Lahore” with Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy (“Saving Face” – 2012 Academy Award winner for Best Short Documentary). The film follows a group of musicians, Pakistan’s Sachal Jazz Ensemble, as they travel from their home to New York City to perform at Lincoln Center. There, they find international recognition after decades of opposition from dictators and religious extremists.

“As a documentary filmmaker you want to find a great story, great characters and a topic that matters to people,” Schocken stated in a press release. “You have to have things happen to create drama and tension, and we were lucky enough to find that.”

Schocken said he is thrilled to bring “Song of Lahore” to his hometown.

“Though I’ve been able to screen the film around the world, there are so many friends and family that haven’t had the chance to see it yet,” he told the Reporter. “And watching it on the big screen with surround sound is just a different experience than watching online.”

The ancient city of Lahore was once the center of Pakistan’s thriving film-music recording industry, but that came to an end in the late 1970s under the Islamist rule of General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. Music was repressed, and though entire families of musicians lost their livelihood, the ancient musical traditions were quietly passed down from one generation to the next behind closed doors.

As government opposition to music eased in the 1990s and 2000s, businessman Izzat Majeed founded the Sachal Studios Orchestra, combining classical Pakistani instruments and techniques with the American jazz he had fallen in love with in the 1950s.

Their innovative versions of jazz standards, most notably Dave Brubeck’s iconic “Take Five,” made the orchestra a surprise Internet phenomenon, earning international acclaim and an invitation to perform at Lincoln Center with jazz great Wynton Marsalis and his band.

Obaid-Chinoy and Schocken document the group’s inspiring journey, as it struggles to adapt to the unfamiliar strictures of Western music and restore Pakistan’s venerable musical traditions.

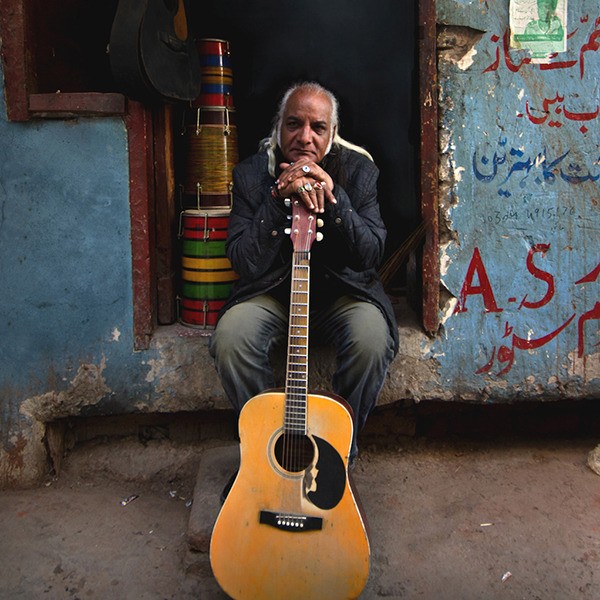

The film focuses closely on a few members of the ensemble, including arranger and conductor Nijat Ali, Baqir Abbas, who plays the flute, guitarist Asad Ali and Saleem Khan, the violinist “who desperately wanted his grandchildren to learn to play the violin, and was afraid the music would die with him,” Obaid-Chinoy stated.

Obaid-Chinoy had spent about a year interviewing ensemble members and filming rehearsals when the group received an invitation to perform at Lincoln Center. Realizing the film would span two distant continents, Obaid-Chinoy decided to enlist the help of an American-based collaborator and was introduced to Schocken, whose credits include co-producing and shooting the Academy Award-nominated “The Last Campaign of Governor Booth Gardner,” a film for HBO about Gardner’s campaign to legalize assisted suicide in Washington.

Schocken faced a major hurdle in not speaking the languages spoken by many of the film’s subjects.

“When you’re making a documentary, the success of the film is totally dependent on creating an emotional rapport with the people you’re filming. Doing that through an interpreter is very challenging,” he stated. “Even in post-production, working with Urdu, Punjabi and English presents a lot of organizational challenges.”

Schocken said he became interested in film after college, having been inspired by the documentaries “Brother’s Keeper” and “Intimate Stranger.” He found an unpaid internship at KCTS-9, assisting Enrique Cerna on a number of KCTS films, and then took an editing job for Seattle philanthropist Sam Stroum. After doing some short films and videos in Seattle, he got his formal training in documentary filmmaking at Stanford.

Schocken said he became interested in film after college, having been inspired by the documentaries “Brother’s Keeper” and “Intimate Stranger.” He found an unpaid internship at KCTS-9, assisting Enrique Cerna on a number of KCTS films, and then took an editing job for Seattle philanthropist Sam Stroum. After doing some short films and videos in Seattle, he got his formal training in documentary filmmaking at Stanford.

“Song of Lahore” is his first feature length film as producer/director.

“My primary work has always been as a cinematographer, so the film has introduced me to a lot of new filmmakers to work with, and opened up new opportunities for collaboration,” he told the Reporter.

The filmmakers hope “Song of Lahore” will help Pakistani audiences appreciate the value of the region’s traditional music and prove that it’s something worth supporting.

“Music is such an international language,” Obaid-Chinoy stated. “It doesn’t matter where you come from or who you are; if you play good music, it’ll get accepted and appreciated by people all around the world.”

Universal Music Classics created a companion album called “Sounds of Lahore.” It is an “East-meets-West” concept project, featuring the Sachal Ensemble performing several traditional Pakistani folk and pop songs, combined with well-known American pop, folk, jazz, rock and blues songs sung by a diverse roster of esteemed and successful Western performers.

It also includes a poem by India’s four-time Nobel Prize for Literature nominee, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, set to original music written by the Sachal Ensemble and read by Oscar-winning actress Meryl Streep.

Beyond introducing Western audiences to a rich and ancient musical tradition they may not have experienced before, the film “Song of Lahore” presents a more nuanced story about Pakistani people than is typically depicted in the media, Schocken stated.

“It’s not about politics. It’s not ripped from the newspaper headlines,” he said. “It is a story about a group of courageous people who have chosen to fight for a better future for their families and to preserve the musical heritage that has brought meaning and beauty to their lives.”