It was 1959 and Nancy Spaeth had just started the seventh grade when it became difficult for her to brush her thick, wavy blonde hair. It also became hard for the relay runner to race, and she noticed that her urine was brown.

A visit to the doctor revealed the problem — the preteen had kidney disease. The diagnosis would launch Spaeth, now 62, on a journey as a pioneering dialysis patient and four-time kidney transplant recipient.

A few months after her initial diagnosis, Spaeth, who now lives on Mercer Island, was admitted to Seattle Children’s hospital for further tests and treatment. She endured remedies that involved high doses of an anti-inflammatory and nitrogen mustard — a chemical related to mustard gas. The treatment caused Spaeth to drift in and out of consciousness and her eyes to swell.

“Eventually, I was awake enough to ask my mother to hold open my swollen eyes so that I could see her,” Spaeth said recently about her ordeal.

She returned to school the following fall and remained active throughout her junior and senior high school years. In the fall of 1965, Spaeth entered the University of Arizona, but by February 1966, she became too sick to stay. She returned to Seattle and continued college at the University of Washington, then transferred to Seattle University.

Back then, treatment for chronic kidney failure was in its infancy. A new treatment involved implanting a U-shaped tube into patients’ arms or legs, which would enable doctors to access a patient’s bloodstream repeatedly. This new device, a shunt, was created by Dr. Belding Scribner of the University of Washington School of Medicine, and it was first implanted into the arm of machinist Clyde Shields in 1960.

Patients in need of ongoing dialysis would need the Scribner shunt, but that was only the first hurdle. Dialysis was expensive and still considered experimental even six years after it was first introduced as a continuing treatment, so a community panel decided which patients would be allowed to get dialysis.

The Admissions and Policy Committee at the Seattle Artificial Kidney Center (the original name of Northwest Kidney Centers) made the determination. “We called it ‘The Life and Death Committee,’” Spaeth said.

Luckily for Spaeth, she was selected for the program and began dialysis at the kidney center the day after Christmas 1966, while continuing to be a full-time college student. After a year and a half of in-center dialysis, Spaeth went through three months of training to begin home dialysis.

Over the course of her treatment, Spaeth was called upon by the pioneering physician to help him forge a good impression with potential contributors. “Dr. Scribner would occasionally call me, saying, ‘Nancy, are you free for dinner on Saturday? Well, put on that black cocktail dress and come down about 6 o’clock,’” Spaeth recalled.

The young co-ed would put on a sleeveless black dress, wrap her arm bearing the shunt with gauze, and head to Scribner’s home. Often Scribner’s wife, Ethel, would serve rib roast with no salt (to make it easy on the diners’ kidneys) and set the table with two wine glasses per guest. “In the two glasses were two different wines — one of his [Scribner’s] good ones and a cheap one from the local store,” Spaeth recalled. The doctor, a wine aficionado, liked to see who could tell which was which, she explained.

Scribner would often depart his own party early, leaving Spaeth and other guests to stay and chat among themselves. “He always went to bed early because he arose quite early. He always did his best thinking the early hours of the morning,” Spaeth said, adding, “I would stay and visit, then explain the early-to-bed routine to the gentlemen.”

Scribner often would call Spaeth a week or two after the dinner and report that they landed the grant. “The first time I went for dinner, I had no idea that it was for a fundraising mission.” Spaeth recalled.

Spaeth graduated from Seattle University in 1970 with a bachelor’s degree in education. She received her first kidney transplant in 1972, and that summer married and subsequently had two children, Joshua and Sarah.

In spite of her chronic illness, Spaeth worked as a substitute teacher for kindergarten through 12th grade for the Forks School District. She returned to college in 1979 and earned a nursing degree. Spaeth’s life since then has been punctuated with repeated kidney failures, transplants and dialysis. In 2000, she received her fourth transplant, with which she is currently living.

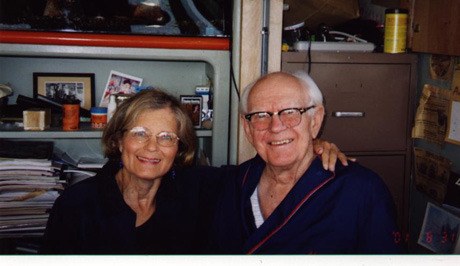

Today Spaeth works as an occupational nurse consultant with the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries, assisting injured workers in their return to work. She serves on the board of trustees at Northwest Kidney Centers, and she frequently gives talks about her experience with kidney disease — focusing on all that can be accomplished, even with a chronic disease.

“You can live long and you can live well with kidney disease,” she said, adding, “I have done it. I worked. I had children. I have a grandson and I’ve traveled … I don’t have any complaints, and I feel very lucky.”

Health experts encourage those in high-risk groups to ask their doctor to monitor their kidney health at every checkup.

Awareness of chronic kidney disease

One in seven American adults has chronic kidney disease with no overt signs.

High-risk groups include those with diabetes, high blood pressure, or a family history of kidney disease; African-Americans, Hispanics, Pacific Islanders, Native Americans and people over age 60.

For more information, visit www.nwkidney.org.