President Lyndon B. Johnson helped end racially restrictive covenants in 1968 with his Fair Housing Act. In the present day, a group of University of Washington students are poring over records to identify racist deed restrictions and restrictive covenants in Western Washington counties.

Through their Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, authorized by the passing of House Bill 1335, the group has thus far identified 20,000 racially restrictive properties in King County, and the list continues to grow.

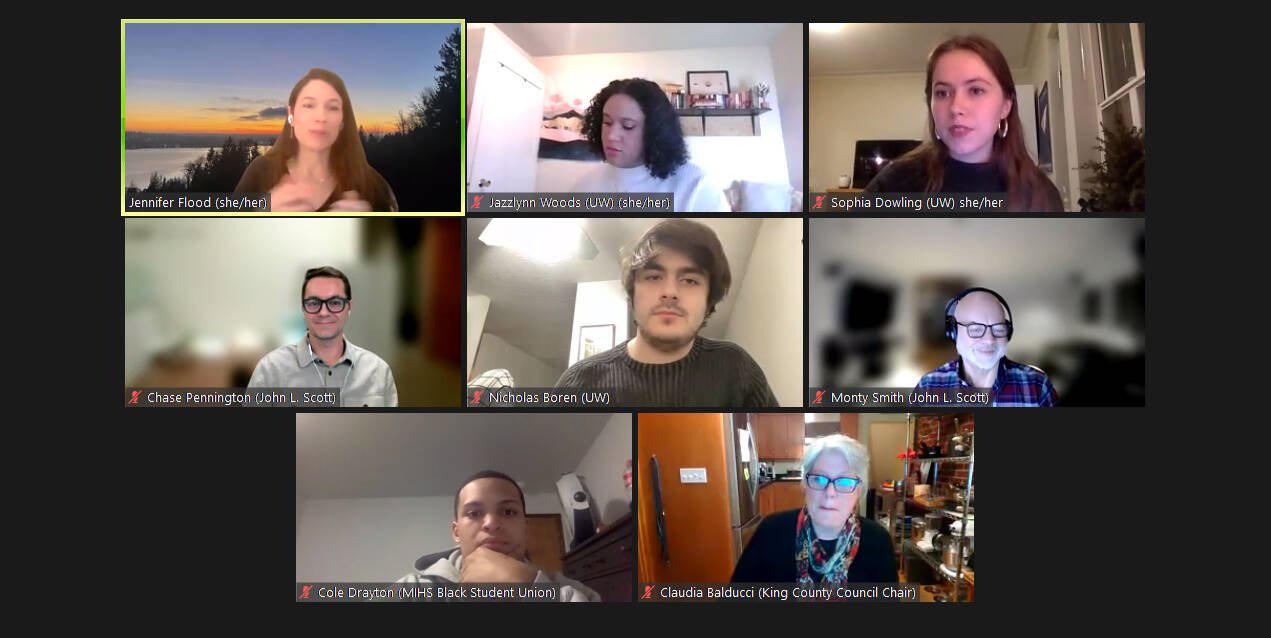

Research associates Jazzlynn Woods and Sophia Dowling and IT research associate Nicholas Boren presented their findings, which include some Mercer Island properties, at the first installment of the city’s Community Conversations series on Feb. 2 over Zoom.

“We as a project think it’s important to recognize this history because this history is still affecting people of color today,” said Woods, who spoke to more than 300 attendees at the event. The Mercer Island High School (MIHS) Black Student Union presented the “Towards Inclusive Community” event in partnership with the city, Do The Work MI, ONE MI and the Stroum Jewish Community Center.

Woods noted that Seattle has a lengthy history of racial discrimination and segregation, and described the covenants as agreements made by property owners, subdivision developers or real estate operators to not sell, lease or rent properties to specified groups on the basis of race, creed, religion or color.

The researchers displayed one plat map showing that the Mercer Island Faben’s Point Water Front Tracts was a racially restricted subdivision.

King County Council Chair Claudia Balducci spoke at the event and brought the impact of the covenants into the present by referencing the eye-opening book by Richard Rothstein, “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America.”

Balducci helped launch a task force in 2017 to study the causes, results and solutions to some of the King County housing challenges.

“We have a housing shortage in this region, but we also have housing inequity in this region. You are about to dive into one of the reasons: historically why that was created, but the tendrils of those historical decisions — in covenants and lots of other policy areas — persist to today. Housing instability and housing insecurity hits our communities of color particularly hard,” she said. “This (event) is how we start to undo those harmful impacts.”

Senior Cole Drayton, vice president of the MIHS Black Student Union, said he is one of 24 students who identify as either Black or African American at the school and added that his organization was honored to be involved with the presentation.

Drayton said the purpose of the event is to “bring awareness to the segregation on the racial covenants of Mercer Island. We just hope this can be one of the first steps to help make Mercer Island a truly inclusive environment for all people who live here.”

A statement presented at the event notes that the Black Student Union hopes that attendees can “understand that redlining created/maintained home ownership/poverty gaps, and separation between white people and minorities which still affects greater Seattle now.”

While discussing the history of racially restrictive housing efforts in the United States, Dowling said that redlining was part of color-coded neighborhood maps devised in the 1930s in which green meant “best,” blue meant “still desirable” and red was deemed “hazardous” based solely on the presence of people of color in the area. Organizations referred to the maps for loan-collecting purposes and believed the loans would be at a much higher risk in racially mixed neighborhoods, she said.

Monty Smith and Chase Pennington of John L. Scott Real Estate joined the presentation and discussed the “Driving Change” project that their company is helping launch in the near future.

When people type their address into a section of the site, it will connect with a public records search and identify where the property is located and if any of their documents contain racially restrictive covenant language.

“If a homeowner saw this and they wanted to effect some change, our tool allows for an easy way to provide a modification to their title,” Pennington said.

For more information on the Community Conversations series, visit www.mercerisland.gov/communityconversations.